Rock Beats Scissors, Hammer, and Sickle

March 25, 2014

Spent most of the morning listening to the Plastic People of the Universe while working on my Bibliography, just to get me in the mindset. What I’ve gleaned? It’s terrible. Certainly no Blink-182 or Ramones. I must be an old Communist, because this music gives me a headache.

The good news is Zotero helps a lot with the Bib. Bad news, I’ve never done Chicago before so I am constantly second guessing myself. It just looks so weird… I can do MLA in my sleep (English major), but Chicago seems just…wrong looking; like I’ve misspelled a word.

Luckily I’ve found tons of sources and I think this paper might actually be coming together.

The Cold War and Punk Rock

March 6, 2014

I’ve been really undecided what to do for my final research paper, but I just realized I’ve been doing the research for weeks now already.

In Carnival of Revolution by Padraic Kenney he mentions big punk rock bands protesting in 1989. I was fascinated by this, and began Googling it right away (not exactly scientific research, which is why it took me so long to realize I had my topic).

I love rock music, and I was excited, although unsurprised, to find it had a voice within the revolution. Now that I know what interests me, I still have no idea what my thesis is. Saying punk rock helped inspire the revolution of 1989 seems too broad to fill up 15 pages. I want to be more specific, have something I actually need to persuade my audience of. So… we’re close but not quite there just yet.

I plan on doing some real research (instead of just aimless Google searches) and maybe scan over some of the readings we’ve done this semester to really try and solidify what I want to say and why rock was important. Meanwhile, any advice would be awesome.

Poetry Matters Too

February 25, 2014

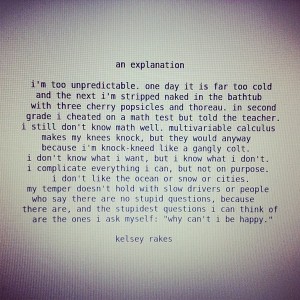

I know I’m mainly focusing on Communism here, but poetry is a lot like Gorbachev, because no one really cares what either one is doing in 2014. So when prompted to analyze a personal narrative, I knew Kelsey Rakes-Jaggers was my girl.

I originally wanted to focus on her blog, but quickly realized I could analyze an actual poem of hers, since most of her poetry is autobiographical and personal.

Kelsey Rakes-Jaggers has often discussed her mental illnesses in both her blog and her poetry over the years, and I think this is a reflection of that. However, I also really think this piece is relatable. Everyone can be overly critical of themselves, and when you’re alone with your own thoughts you think of one bad quality and spiral downward into “EVERYTHING ABOUT ME IS TERRIBLE.” Otherwise, it’s hard to summarize this piece. I think it really speaks for itself. It is about emotion, and it is about humanity. It won’t change a nation or inspire a rebellion, but I think it could comfort a reader and really leave them thinking. Kelsey Rakes has often asked, “is happiness just the absence of sadness?”

Rakes’s poetry doesn’t speak about any historical events in this poem. It’s not a fact. It doesn’t rhyme, she never uses capital letters (in any poems) and it doesn’t even have stanzas. Nevertheless, this is postmodern poetry. The work she is having published is an extension of models enforced by Charles Bukowski and much of Leonard Cohen, but she is the next generation. Poetry today isn’t about counting syllables; Robert Frost was great, but it’s time we moved on.

Most importantly, Rakes believes in online publishing, often through several mediums. The example above was originally published on Instgram, but she also Tweeted it out, published it on Tumblr, and features it in on DeviantArt and both of her blogs. She has a very large online following.

Today we’re studying propaganda posters and political newspapers to learn about history. In twenty years, we will be studying Twitter feeds and blogs. Having that sort of information at our fingertips for free is something Kelsey Rakes-Jaggers really supports, and I think it’s a fascinating way to learn how our history is changing right before our eyes.

A Haunted Present

February 18, 2014

I want to clarify, before I start, that in no way did I dislike Tina Rosenberg’s The Haunted Land. The book, rather than collecting events that lead to the fall of the wall, attempt to gather a history to be collected on how citizens survived through Communism, and how they plan to tackle the future.

Rosenberg argues, as most of us have heard before, that history is written by the victors. Yet the complicated part with Eastern European Communism is deciding who the victors were in a region seemingly filled with docile citizens changing their stories with political popularity. She attempts to interview prominent figures in three different regions (Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Germany) to discern how each one might change their views of the revolution as time passes.

My criticism is this: not enough time has passed. I initially found it rich that Rosenberg attempted to garner how history would be written only a couple of years after the fall of the wall. The book is published in 1995, meaning much of the chaos and uncertainty she alludes to could be resolved. Of course a country would spend half of a decade pointing fingers and scrambling to piece back together a union. I can only imagine how transitioning from communism to democracy could be difficult, both for citizens and for governments. Yet Rosenberg takes a critical approach to these people, often insisting they contradict themselves and change their stories. Her conclusion being, of course, that history is unreliable and biased.

Yet I began to realize Rosenberg writing this so soon after the revolution of 1989 was actually what makes it so useful. If I attempted to write this book now, 25 years later, not only would I lose direct access to as many primary sources, I would find a rehearsed narrative. Rosenberg’s book is less about writing the history of the fall of Eastern Europe, where I think several other books have already achieved. Rather, her book is an examination on how history is made. Whether her assertions about Eastern Europe politics and opinions on the Stasi files hold up today are irrelevant. It is more incredible to see history unfolding, year by year, to form into what anyone can read today.

Rosenberg’s book had to be written so soon after the revolution, because it is the closest thing to accurate many could find.

A Carnival Against Communism

February 11, 2014

A Carnival of Revolution by Padraic Kenney examines the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe (or Central Europe as Kenney calls it) in 1989. His main argument is that no one series of events brought about the collapse in 1989. Many people, even today, call the year 1989 a “miracle” or a “sudden surprise”. However, Kenney argues it was a revolution with a long time coming, sometimes 20 years in the making.

The Walls Came Tumbling Down by Gale Stokes examines the same time period, but takes a much different approach. Both books explain a myriad of causes leading to the year 1989, but Stokes offers a more linear approach, suggesting most everything through the 70s and 80s had a cause and effect, but Kenney’s work offers a much more complicated turn of events.

The novel begins with an intro titled “Concrete Poetry” and continues in that metaphor–quickly swaying between countries and years and topics merging them all together in a hodgepodge (or carnival) that eventually sparked the collapse of 1989. Between interviewing actors and workers, Kenney paints the pluralism and multitude of agendas that moved, not necessarily against communism, but towards improvement. The movements of the book between subjects and events serves, like concrete poetry, to show the confusion and multitudes of the actual decade before the revolution.

While Stokes uses headlines and news stories to paint a broad picture of Eastern Europe, Kenney takes his audience on a much more complex and in depth journey. Therefore, I think it’s crucial that I read Stokes before Kenney. Stokes helps even the most ignorant of readers (me, for example) understand the broad overlays of the revolution of 1989 and its causes. Kenney, meanwhile, shows the chaos of the grassroots movements (because there were certainly several agendas) and how the uprisings of 1989 were, by no means, a surprise.

Primarily Accurate

January 28, 2014

The difference between primary and secondary sources is clear, and Robert Darnton’s recounting of “The Great Cat Massacre” is an example of this. The story itself is a secondary source discussing a primary description of an apprentice’s experience as a printer.

The story discusses the slaughter of several stray cats while other workers of the shop looked on and laughed. It horrified me, which Darnton explained shows the difference between my own experience and views compared to the apprentice. The space of time between primary and secondary sources has never been so evident to me until now.

With this in mind, I examined some other primary sources, specifically from the site Making the History of 1989

The poster is meant to symbolize American ideals to contrast the opponent in an upcoming Polish election. Despite being completely unfamiliar with the movie High Noon I clearly understood the tough western cowboy and what he represents in my own culture. However, without the background explanation the site offers (a secondary source) I would be unable to interpret or comprehend this image at all.

I accounted similar problems when confronted with anarchy pamphlets from 1989. I don’t speak German, but I recognize the Solidarity slogan again from the poster. I also recognize universal symbols such as the capital A for anarchy and peace signs.

I realized in this activity I’m positively useless at interpreting primary sources. I think it is difficult to understand something without present day context and explanation. If the articles were in English it might be easier to glean more information. Furthermore, if I knew more about the time period I could take more from these sources. However, that would be a secondary source.